Imbolc (Imbolg) - Cross Quarter Day

Imbolc or Imbolg (pronounced im-olk) is the festival marking the beginning of spring and has been celebrated since ancient times. It is a cross quarter day, positioned midway between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox.

When calculated as the midpoint between the astronomical

Winter Solstice and the astronomical

Spring Equinox, Imbolc generally falls between the 3rd and 6th of February.

This astronomically derived date is later than the traditional observance on February 1st.

Imbolc is often mistakenly assumed to fall on February 1st, which is St Brigid’s Day.

When calculated as the midpoint between the astronomical

Winter Solstice and the astronomical

Spring Equinox, Imbolc generally falls between the 3rd and 6th of February.

This astronomically derived date is later than the traditional observance on February 1st.

Imbolc is often mistakenly assumed to fall on February 1st, which is St Brigid’s Day.

Imbolc derives from the Old Irish i mbolg meaning in the belly, a time when sheep began to lactate and their udders filled and the grass began to grow.

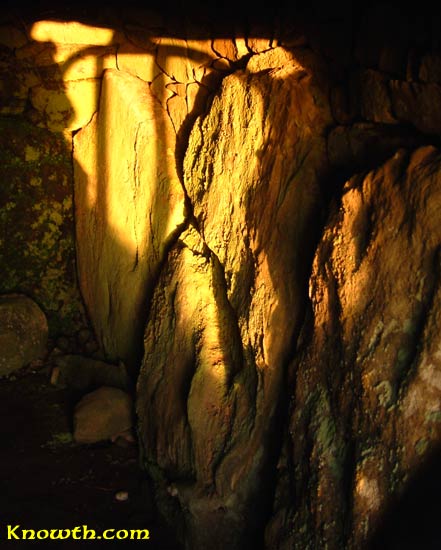

At the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara the rising sun at Imbolc illuminates the chamber. The sun also illuminates the chamber at Samhain, the cross quarter day between the Autumn Equinox and the Winter Solstice.

The Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara is a Neolithic Period passage tomb, contemporary with Newgrange which is over 5,000 years old, so the Cross Quarter Days were important to the Neolithic (New Stone Age) people who aligned the chamber with the Imbolc and Samhain sunrise.

In early Celtic times around 2,000 years ago, Imbolc was a time to celebrate the Celtic Goddess Brigid (Brigit, Brighid, Bride, Bridget, Bridgit, Brighde, Bríd). Brigid was the Celtic Goddess of inspiration, healing, and smithcraft with associations to fire, the hearth and poetry.

When Ireland was Christianised in the 5th century, the mantle of the Goddess Brigid was passed on to Saint Brigid, born at Faughart, near Dundalk, Co. Louth.

She founded a monastery in Kildare and ended her days there. The Goddess Brigid festival was Christianised to become Saint Brigid's Day.

When Ireland was Christianised in the 5th century, the mantle of the Goddess Brigid was passed on to Saint Brigid, born at Faughart, near Dundalk, Co. Louth.

She founded a monastery in Kildare and ended her days there. The Goddess Brigid festival was Christianised to become Saint Brigid's Day.

The Saint Brigid's Cross is one of the archetypal symbols of Ireland. While it is considered a Christian symbol, it may well have its roots in the pre-Christian Goddess Brigid. It is usually made from rushes and comprises a woven square in the centre and four radials tied at the ends.

The Saint Brigid's Cross was traditionally hung on the kitchen wall to protect the house from fire and evil. Even today a Brigid's Cross can be found in many Irish homes, especially in rural areas.

In Christian mythology, St. Brigid and her cross are linked together by a story about her weaving this form of cross at the death bed of a pagan chieftain who, upon hearing what the cross meant, asked to be baptised.

Gerald of Wales reported in the 12th century that a company of nuns attended an 'inextinguishable' fire at Kildare in St. Brigid's honour. Although it had been kept burning for 500 years, it had produced no ash. Men were not allowed near the fire.

According to myth, Saint Brigid travelled to Glastonbury and set up a small chapel on Bride's Mound. She is one of the four holy people celebrated with a small stone monument in the Glastonbury Tercentennial Labyrinth.

Celtic Goddess Danu

The author Felicity Hayes-McCoy links St. Brigid to the Celtic Goddess Danu.

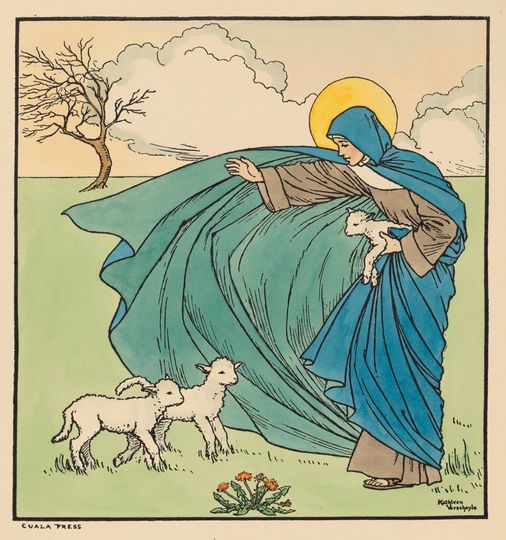

The stories associated with St. Brigid are echoes of the ancient story of the Goddess Danu. Danu's people were tribal Celts who brought her worship with them to Ireland along with their skill as herdsmen and their knowledge of farming crops. Danu was their fertility goddess whose powerful energy revitalised the earth each year in spring. There are stories of seeds waking to the pressure of her feet, and flowers springing up where her cloak touches the fields.

She was a powerful personification of fertility and in Celtic mythology, her marriage to the shining sun god Lugh combined the elements of light, heat and water which brought life to the fields in springtime. Danu's name means 'water'. Without water nothing can grow so, for the Celts, she was an image of the essence of life itself. And she's the prototype of the medieval St. Brigid, who controlled the weather, cured infertility, blessed the housewives' labour and increased the farmer's herds.

Alternative Chronology

The chronology of Celtic Goddess Brigid transposing into the Christian Saint Brigid is not universally accepted. The first mention of the Goddess Brigid in Irish literature is in Cormac's glossary from the 10th century. There is no mention of the Goddess Brigid in the 8th to 10th century Mythological Cycle. So it could be argued that 5th century Saint Brigid predates the Goddess Brigid.

What do we know about the roots of the Imbolc spring festival?

By Kelly Fitzgerald, UCD

Imbolc or Imbolg (amongst many spellings of the term) is often referred to as the calendar custom which was an earlier Irish, pre-Christian or pagan festival that was celebrated on the first day of spring. It is often seen that St Brigit's Day replaced Imbolg and that Brigit’s Day is the only Christian name given to a Celtic Quarter Day. The three other days in the year include Béaltaine on the first of May, Lúnasa at the beginning of August and finally Samhain at the end of October beginning of November.

Imbolg may also be seen to have been replaced in the Christian calendar by Candlemas, a date also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter. Candlemas Day is another name for the feast of the Presentation of the Lord when 40 days after his birth, Mary and Joseph brought Jesus to the temple for the rites of purification and dedication: After Candlemas rough was their herding.

The Irish term for milking, bliged, can be seen to derive from the earlier term mligid and it has been put forward that the term Imbolg is based on that term. Often a cited source for information on some of the oldest traditions in Ireland, Cormac's Glossary is usually ascribed to Cormac mac Cuilennáin (d. 908), king-bishop of Cashel and its entries list a large number of old and rare words, including names from Irish literature.

Here, we find that earlier analysis of the term has found the term for 'sheep' incorporated into the meaning of Imbolg. It has been that is to say this is the time when sheep bring forth milk, that is to say, hence to milk.

Modern academic scholars have so far failed to reconcile lexically the supposed constituent elements of oimelc (imbolc/ imbolg). It has been suggested to not contain two words, but one single word for 'milking.' Etymologiae (Etymology) is the best known work by Saint Isidore of Seville (circa 560-636), a scholar and theologian considered the last of the great Latin Church Fathers. It takes its name from a method of teaching that proceeds by explaining the origins and meaning of each word related to a topic. Influence from Isidore’s Etymologiae may have brought in the connection with sheep into the Irish analysis.

The 'Coligny Calendar', dating from the end of the second century C.E, was discovered in Coligny, France, and is now on display in the Palais des Arts Gallo-Roman museum in Lyon. It dates from the end of the second century. The calendar was originally a single huge plate, but survives only in fragments and is inscribed in Gaulish with Latin characters and Roman numerals. The Coligny calendar may possibly refer to the time from January into February as a month of horses or livestock, otherwise animal husbandry and from February until March continues on with attention to the animal world with the month of the stag.

References to Imbolg in early Irish literature refer to it as 'after the feast of Brigit' or 'until the beginning of spring', clearly separating it from the actual saint’s day on the first of February. It has been suggested that the lack of inclusion of a term such as Imbolg in the Stowe recension of the Táin may be due to the fact that the term was outdated or unfamiliar in the 15th century when the manuscript was transcribed. The term Iomfhoilcc is found in a 17th century manuscript of Agallamh na Seanórach and may be seen to have taken on to refer to the Irish word folc, 'to clean or wash'.

Referring back to the Christian feast of purification or Candlemas on February 2nd or after the feast of Brigit, when we think of candles, literally the wording found in Candlemas 'the mass of candles', we often think of the feast day of St. Blaise. On February 3rd, the Church recalls a miracle cure associated with him and celebrates the blessing of the throats with candles. St. Blaise said that anyone who lit a candle in his memory would be free of infection, thus candles are used in the traditional throat blessing.

A later version of Tochmarc Emire, 'The wooing of Emer', a tale in the Ulster cycle, connects Imbolg to the beginning of spring: …that I shall fight without harm to myself from Samain, i.e., the end of summer. For two divisions were formerly on the year, viz., summer from Beltaine (the first of May), and winter from Samuin to Beltaine. Or sainfuin, viz., suain (sounds), for it is then that gentle voices sound, viz., sám-son 'gentle sound'. To Oimolc, i.e., the beginning of spring, viz., different (ime) is its wet (folc), viz the wet of spring, and the wet of winter. Or, oi-melc, viz., oi, in the language of poetry, is a name for sheep, whence oibá (sheep's death) is named, ut dicitur coinbá (dog's death), echbá (horse's death), duineba (men's death), as bath is a name for 'death'. Oi-melc, then, is the time in which the sheep come out and are milked, whence oisc (a ewe), i.e., oisc viz., barren sheep.

Connections to Brigit, spring, cattle and animal husbandry may demonstrate why so much of this material has become conflated over the centuries. From the very beginning, we cannot move away from the fact that the material we have at hand may not be treated as unbiased sources.

The earliest medieval sources are trying to figure it out themselves. Brigit’s associations to the milking of cattle, her role as 'Mary of the Gaels' and becoming an actual manifestation of bright lights connected to candlelight cannot be discounted in how the folk imagination recognises the importance of such matters at this time of year. The folk narrative may not have felt the need to keep all matters separately, as we may wish they had, but we cannot deny the significance of recognising the coming of spring. The cold, long winter may not be over, but we will get there, eventually.

Kelly Fitzgerald would like to thank the many scholars that have worked on Imbolg over the years that have contributed greatly towards this piece.