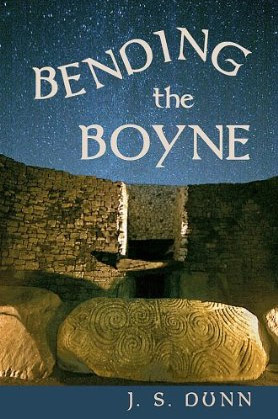

Bending The Boyne: A novel of ancient Ireland

Bending the Boyne by J.S. Dunn. The novel is

based in ancient Ireland about 2200 BCE. The author J.S. Dunn became interested

in the megaliths of the Boyne Valley and who built them and why. With the coming

of metals and marine traders, the communities and mounds fell into disrepair.

Bending the Boyne tells the story of what happened, drawing on the

rich characters from early mythology: Boann, the Dagda, Cian, and others.

Bending the Boyne by J.S. Dunn. The novel is

based in ancient Ireland about 2200 BCE. The author J.S. Dunn became interested

in the megaliths of the Boyne Valley and who built them and why. With the coming

of metals and marine traders, the communities and mounds fell into disrepair.

Bending the Boyne tells the story of what happened, drawing on the

rich characters from early mythology: Boann, the Dagda, Cian, and others.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Bending the Boyne draws on 21st century archaeology to show the lasting impact when early metal mining and trade take hold along north Atlantic coasts. Carved megaliths and stunning gold artifacts, from the Pyrenees up to the Boyne, come to life in this researched historical fiction.

2200 BCE: Changes rocking the Continent reach Eire with the dawning Bronze Age. Well before any Celts, marauders invade the island seeking copper and gold. The young astronomer Boann and the enigmatic Cian need all their wits and courage to save their people and their great Boyne mounds, when long bronze knives challenge the peaceful native starwatchers. Tensions on Eire between new and old cultures and between Boann, Elcmar, and her son Aengus, ultimately explode. What emerges from the rubble of battle are the legends of Ireland's beginnings in a totally new light.

Larger than myth, this tale echoes with medieval texts, and cult heroes modern and ancient. By the final temporal twist, factual prehistory is bending into images of leprechauns who guard Eire's gold for eternity. As ever, the victors will spin the myths.

In the following extract the intruders are the Beaker people who arrived and camped at the Boyne mounds which we know today as Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth.

Extract from Bending the Boyne

The flaming head of the ancient one tipped above the horizon. The rising sun took Boann into its warm, golden embrace. She stayed until the rays hid the glittering void, ending her vigil of the stars. All in her village would be stirring and she should return to her father's house. With longing, she glanced back toward dawn over the waves.She saw it then, a speck out on the vast ocean. With her hand shading her eyes she could see the large boat, crammed black. Sparks of light glinted from metal: the fearsome long knives.

Boann scrambled down the mountain slope to warn the Dagda. She soon found him, a dignified figure herding sheep and lambs on the grassy river plain.

"You're sure that it is an intruder boat?" He cast a wary look to the east.

She nodded. "I am sure that I'm sure."

"What can this mean? Arriving with equinox, the cursed warriors!" The Dagda raised his staff, its red stone macehead gleaming. "I'll rouse the elders and send our scouts."

He sped away on his long legs, leaving the surprised flock milling around her.

Never had she seen the Dagda swear, or run as he did now. His news would cause turmoil in their village. She had better fetch water before returning there. Feet flying, she hurried north to the smaller river.

Mist hung thick over the stream. In the grey stillness, she thought herself alone. She retrieved her clay pot among ferns, lifting their damp scent with it. Auburn hair cascaded over one shoulder as her torso leaned toward the water to fill the jug. Another time she might have glimpsed her face on the water's placid surface but now she paid it no heed. A bird twittered and flapped in the copse, and her head jerked up, alert.

Behind her a twig snapped under heavy footfall, then another. She felt the noise, she heard it to her core: danger. She spun around, eyes wide, and a pungent odor struck her nostrils. A bulky shadow lurched from a stand of hazelnut and her every muscle leaped into action. His knife sliced at her net shawl but she pulled and ran away from the smell, away from the intruder. She outpaced his shadow, leaving branches whipping behind her in the mist.

She gripped the fragile pot while her legs raced through gorse and bracken and over rocks, this way and that. Only a fox could have pursued her. After a good distance, Boann broke her stride, sank into dense undergrowth, and listened. Other than her ragged breathing, a strange quiet smothered the woods.

Shaking, she rose and stared down at the water jug in her arms. My mother's favorite. Head spinning, she fought an urge to be sick. Her legs stung from nettles. Water blotched her soft skin tunic and thorns had scraped it. Her good shawl lay somewhere behind, ruined. She'd have another, Sheela could make her another shawl but not by this sunset.

Sure that no one followed, Boann turned and found a path that led to the dwelling shared with her father. She slowed to a walk, heart still racing.

Glad she was to reach their home, its old but solid walls of drystacked stone. She left the slab wood door open behind her and slipped inside. Hearth smoke furled up through the roof hole in the thatch, silently reminding her to appear calm before her father Oghma. Ever since her mother had passed to the spirits, his temper could flare. She heard Oghma fussing with his mallets and stone chisels behind a woven willow screen, already up and about.

She swallowed hard; what could she do to distract him before telling him about the boat, much less her attacker? Her quick hands took pieces from braids of drying flowers and potent herbs. She threw hot stones into a skin bag of water to set it boiling and snatched up a clay cup incised with chevrons, the symbol for the Swan stars. Boann admired the cup as her father entered the room.

"Is it herbal water you're having? Are you taken ill?"

"It is close to my time with the moon. The brew eases me." She stepped in front of the emptied water jug lying at her feet. Not even a sharp look came her way. She took a deep breath and told him. "Another big boat arrives. Just so, with spring equinox." Boann stood still as a deer, deflecting scrutiny.

"Yes, the Dagda stopped here in haste. More of them, it hardly seems possible! Perhaps now Cian will return to inform the elders. He is long overdue." His mouth set in a hard line.

So the news of another boat shook Oghma as well. He did not speak of Cian to her, had not mentioned him during all the winter. She would not tell her father that she had been on the mountain with Cian through the night. Already that seemed long ago.

"We must go on as we have done. Why would these intruders bother us on the equinox?" She hadn't meant to sound defiant, the wrong note with him; she exhaled slowly.

"The Dagda and I agree that the people should gather to celebrate. With Cian, or without him."

With or without you.

Before she could bring herself to tell him of her attacker at their stream, her father said he must be going. His expression softened. "We'll just have to be ready for them. Our scouts left for the coast." Oghma patted her head as if she were still a child, and set out to join the Dagda and the other elders. At the open door, dust motes swirled in the early light: her bits of hope dashed to the floor only to rise and float again.

Her people must hold their ceremony. Their village at the river Boyne led the starwatching, the center of a network whose strands connected all the tribes on the island, tensile yet strong like a spider's web. A tear in the right place could bring down our web; she shivered and moved closer to the hearth fire. They must hold their spring rites and mark the equinox stars. All the elders would have to agree on it, though. Estranged from the elders as he was, Cian might not return that evening.

The elders including her father supervised at the immense stone-lined passage mounds set in clearings, three emerald mounds spaced in a rough triangle along the wide river plain.

Their Boyne starwatching complex had been active for centuries. The ancestors who dreamed and planned these mounds were long deceased. Their descendants completed the work in stages and returned to older villages in the northwest, or began new villages elsewhere. Final alignment and carving of the stones proceeded bit by bit.

Many Starwatchers declared that their grand mounds at the Boyne would never be duplicated. And, replied some, these mounds would never be finished. Their banter belied an unspoken fear. Fear had arrived with the intruders and their long bronze knives.

* * *

The village hummed with talk of more intruders arriving. A community of herders, basketmakers, netmakers, toolmakers, scrapers and tanners, and not one among them who'd fought in battle. Oghma saw his people working with a new urgency. He nodded at the bowmaker who was steaming pliant yew for bows, and again at the young man close by hewing hard ash for tools. The latter put down his flint adz and caught up with Oghma.

They had gone but a few steps together when the toolmaker asked, "Is there any word from Cian?"

Oghma shook his head.

"I don't mean to trouble you."

"It's no bother, Tadhg."

They stopped and faced one another, the toolmaker visibly tense. Oghma placed his hand on the younger man's shoulder. "Some wood has flexibility and some has strength. Let us hope that Cian has both qualities."

The two men regarded each other. "If he lives," Tadhg said. He clasped Oghma's arm briefly, then Oghma moved on.

His people had little use for making weapons. Stacks of hides, rushes, willow stems, wool and bast, sinew and bone, awaited their artful hands. All, even scraps, would be made into useful items. He saw a woman, hair greying at her temples, bundling rushes to make a broom. It would have a sleek wooden handle, welcoming to the touch. He blinked hard, flooded with a vivid memory of his wife sweeping the flags around their hearth, and turned away.

He looked to see that livestock had been secured inside holding pens. He checked stores of cereals and roots, and hid his dismay at their depleted food supply in this young season of the sun. That meager amount would have to suffice in the event.

Villagers interrupted him with whispered queries about the boat sighted at dawn.

"The scouts will tell us where they landed, and how many of them." Oghma reassured each person, not mentioning Cian, and making his voice sound confident.

He ordered a few young fellows to break from what they were doing and help Tadhg make pikes, wood poles sharpened into a spear point. "We may need those, and soon."

At the far edge of the clearing around their dwellings, he came upon the open pit fire where their potter fired her vessels. Her ritual acts with fire transformed raw clay into ceramic. Pots held water and food essential for life, and pots enfolded their death-ashes. The wet smell of the clay and the coals' peaty aroma mingled and reminded him of women, of good things cooking, of the hearth. Transfixed, Oghma watched the potter's agile hands.

From the pliant brownish-red clay, she shaped a bowl with wide shoulders and squat body, then smoothed this pot with a curved bone and set it aside to cure. She was young and pretty but focused on her work, like his Boann.

"A pot created on this dawning holds good luck," he said.

She looked up and smiled. "May this equinox favor us all, Oghma. Your visit honors me."

He smiled in return, putting on a glad face for her. "Fair lass! Have you decided yet on a marriage?"

"Has Boann chosen, and is there any man left for me?"

"You'll both be spoiled for choice this evening," he teased her back.

She picked up a cured pot to decorate its leathery surface, and he caught his breath. If the vessel were less than perfect, the potter must discard it and begin again. Using a bone comb, she made intricate grooves meet flawlessly around its girth. The master potter showed her well-before taken by the fever, and now who could she take on as her own apprentice? He helped to stoke the kiln then wished her luck again, secretly humbled. Unlike her firing of clay, he didn't have to risk putting his handiwork into hot coals.

He hurried on toward the river, to their sacred landscape of mounds that proclaimed the Starwatchers' beliefs. These huge mounds stood taller than a tall tree and spanned many trees across. His carving with stone chisel and mallet gave meaning to the mighty upright stones lining the passages and to the boulders forming the high kerb around the outside. His painstaking labor suited Oghma, it contented him.

But on this equinox, the impending boat loaded with men and deadly weapons from afar irritated him like a thorn. The foreigners' small camp on the southwest coast of Eire, far from the Boyne, had not seemed a threat. For a time, Starwatchers accepted the intruders' seasonal presence and their odd probing in the earth. Upon seeing copper, the Starwatchers hoped to learn how these strangers turned red-hot stones into a material that shone like the sun and cooled to the color of a shadow moon. They allowed the miners to come and go in peace at that far coast. Then with the past summer, armed intruders appeared in their bloated ships at the Boyne's mouth and traveled inland.

Starwatcher scouts followed the strangers who searched along the Boyne, poking at outcroppings and leaving behind piles of shattered and scorched rocks. Scouts monitored the dirty smoke rising from inside the intruders' new camp. The intruders wandered ever farther from their camp and began to take cattle and game as they pleased, despite the coming winter.

Starwatchers avoided contact, fearing the metal knives-and fever. His people suffered. The strangers brought the death of his wife and others, too many others. Then Cian quit his own people to live among the warriors, a thing almost unthinkable. What should be done to protect their children? Should the Starwatchers confront these intruders? The elders deliberated and watched the intruders' comings and goings.

Will we tolerate another boatload of armed strangers, Oghma asked himself.

His green eyes were clouding, his stone chisel slipping in his hand. Over his seasons, he buried two wives, and of his children only Boann survived. Twice as many Starwatcher men survived beyond the age of twenty-five suns than did women; his people cherished their scarce women, and all children. He had lived a long time and only the Dagda counted more suns among those at the Boyne. While a young man, Oghma measured in the night skies and tracked daylight with the astronomers. Led by his mentor who was descended from the revered ancestor Coll, he learned to style the stones at the great starchambers with crisp precision, completing work on each stone at fairly regular intervals. But that was decades ago.

Through that dark winter, he grieved but continued carving at the mounds, as resolute as the raindrops wearing down the island's granite slopes. Pain shot through his joints in the damp chill, his shins stuck to the freezing soil as he knelt. His lean shoulders became stooped, and his thick dark hair whitened. Oghma toiled on in order to finish carving the massive kerbstones, with a quip to the Dagda that the stones might finish him first.

All his hopes rested on Boann. In time, he might see his grandchild. He was glad enough to see newborn lambs and the promise of flowers on this bright morning of the spring equinox.

When he learned from the Dagda's lips of the untimely boat, he told the Dagda, "We people of Eire want for nothing. We have mastered the rhythms of the soil, of the salmon from the ocean, and especially those of the sky. Even the least clever among us know how to prosper here. From sun to sun, we produce enough to sustain us while we study the heavens. We should celebrate spring equinox, our time of planting signaled by the Seven Stars."

The Dagda agreed. "Despite our trials, we can show gratitude for spring's arrival. Never mind what the ocean brings to our shores. On land these intruders cannot travel any faster than Starwatchers."

How many warriors arrived this time? They trusted in their scouts and the Starwatchers who lived at the coast, to alert the Boyne. Oghma hastened along the path to the mounds, his brow furrowed.

The Dagda told him that it was Boann who sighted the new boat bristling with more intruders and weapons. She'd rushed from Red Mountain to tell the Dagda, then she rushed to bring water from the stream, Oghma told himself. That would explain why Boann looked so rattled, something amiss. He did not want to pry. She returned with little water, but he brushed that aside, a trifling thing. At least she'd had a fine sunrise to watch. It did trouble him that she watched many a sunrise and sunset, more than her share. She displayed little interest in any of their young men.

"She secludes herself more and more with the astronomy. That's not a healthy state of affairs for a young woman," he told the Dagda. "Often when I speak to her she doesn't hear me."

"Don't you see it? She takes after you, she escapes in the stars and her work," the Dagda said. "She's had the same losses, after all. Give her time to recover, let her spirit heal."

He heard the Dagda's kind and good advice like a thunderclap. So that was it, Boann still grieved for her mother, as did he. As to Cian's absence, Oghma saw little reason for Boann to feel any loss. He had but faint hope for his apprentice, an indifferent pupil of stone carving, a dreamer. But surely Cian would respect the equinox, rejoin his people at their starwatch.

The young people would dance in the firelight and pair off in the ritual of spring. Perhaps a young fellow from another village would catch her eye. But not Cian, that one would never do for Boann. Oghma tutted disapproval.

Cian once asked him, why did the ancestors build their great mounds? Not "how," he recalled the question, but "why." Oghma did not answer. It was better for young Cian to find his own answer to that question.

The ancestors' history told Oghma precisely why they built their mounds. To ready himself for the equinox, he recited their tradition now on his way through oak woods to the passage mounds. He recited verses of their deeds and lineage as they would have been told to Cian, and all Starwatchers. Back to Griane, our first astronomer, he thought. Griane, who set the first upright marker stone to show us the seasons of the sun and freed us from hunger. Oghma offered a short invocation for the spring sunset that all Starwatchers would observe that evening.

"May the coming season bring us bounty, thanks be to Griane."

He waved away a cloud of midges under the oaks' emerging yellow-green canopy. From the corner of his eye, he saw a red fox flash through the undergrowth. "It is an honor to carve the stones!" he called after it. Could Cian change his shape into a fox? Oghma snorted. What nonsense these intruders do believe: shapeshifting. He flicked his hand again at the midges. Fox or not, Cian could have warned us that more foreigners would arrive.

There stood the warrior camp, visible when he approached the central mound's clearing, and he frowned at this affront on their landscape. He liked to rest beside the Boyne at twilight and gaze at the central starchamber, at its shimmering white quartz around the dark granite entrance. These days his view was partially obstructed by the intruders' camp: a banked, circular earthwork topped with a palisade of crudely peeled logs. The camp's size and fortification spoke a threat from a hostile presence, a threat that his Starwatchers had yet to assess.

The Starwatchers' pikes would be useless against those high walls. Oghma knew it, sure as the sun made little green apples. He implored the ancestors for wisdom to guide the elders.

At the standing stone to the southeast of the central mound, he spotted the elders talking and laying out sightlines for that sunset using cord stretched between wood posts.

"Once in every generation was often enough to receive visitors from far across the waves. These haven't brought any women or polished axes to exchange. Just what have these latest blow-ins brought to us?" Oghma heard the question as he joined them.

"We'll find out soon enough," came the Dagda's reply, calm and deliberate.

"We made the right decision to go forward with the equinox feast," Oghma added. He saw the children playing in the clearing, laughing and running in the misty morning. With a premonition, he saw it all as if held inside a chunk of clear quartz: his villagers bent to their tasks, their precious children beside the flowing river, their carefully constructed mounds.

Oghma would make sure that the children assembled enough reed torches before dusk. After watching the stars in utter dark, the people took up torches so that no one need stumble on their way back to the village. He would supervise stacking the wood for the great bonfire to be lit after their vigil, the signal to Starwatchers at distant sites. If the adolescents collected wet or green wood, their beacon fire would be smoky and its effect diminished.

He would see to it that the Boyne fire blazed when it should with the other fires, lit first at the island's center, its navel, and then to the four sacred directions. He would see Boann enter into the ranks of their astronomers. He raised his head in pride.

"Let these intruders see our fires, and hear our pipes and dancing."

"And if their warriors venture forth?" the Dagda asked.

No one had an answer.

2010 J.S. Dunn, USA. All rights reserved.

Bibliography

Bending the Boyne Bibliography of recent academic books and journal articles in mythology, archaeology, archaeo-genetics, archaeo-linguistics, metallurgy, and ancient astronomy practices and seafaring. Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.ukBoyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Visitor Centre

| Tours

| Winter Solstice

| Solstice Lottery

| Images

| Local Area

| News

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Articles

| Art

| Books

| Directions

| Accommodation

| Contact