Death in Irish Prehistory

Death in Irish Prehistory

by Gabriel Cooney is a book about life and death over 8,500 years in Ireland. It explores the richness of the mortuary record

that we have for Irish prehistory (8000 BC to AD 500) as a highlight of the archaeological record for that long period of time.

Death in Irish Prehistory

by Gabriel Cooney is a book about life and death over 8,500 years in Ireland. It explores the richness of the mortuary record

that we have for Irish prehistory (8000 BC to AD 500) as a highlight of the archaeological record for that long period of time.

Because we are dealing with how people coped with death, this rich and diverse record of mortuary practice is also relevant to understanding how we deal with death today, which is just as central a social issue as it always was.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

"This well-written and beautifully illustrated book is a valuable and extensive presentation of death in prehistoric Ireland and beyond. The way Cooney explores long-term patterns by moving between the past and the present is inspirational."

Anna Wessman, Professor of Iron Age Archaeology, Department of Cultural History, University Museum of Bergen.

Review by Clodagh Finn printed In Irish Examiner, 4 November 2023

Sometimes it is the tiniest detail that stays with you. In 2004, when archaeologists excavated the remains of a young woman buried some 2,000 years earlier at Rath in Co Meath, they found she was wearing a decorated ring on the fourth toe of her right foot.Two near-identical spiral rings, made mostly of copper, were also found on each foot. They were thought to be attachments for the sandals she was wearing when she was laid out, on her right side, with her head facing north-west.

She lived her life in the area, or so isotope analysis suggests, and she stood about 5ft 2" tall. We will never know her name, but it is clear that this young woman was treated with respect and dignity when she died, at some point between the first century BC and the first century AD.

You don't hear much about the Iron Age in Ireland - not in general discussion anyway - so it is fascinating to see the funeral ceremony of that young woman so evocatively described by Gabriel Cooney, emeritus professor of Celtic Archaeology at UCD, in his new book Death in Irish Prehistory.

He imagines what took place one wet day, two millennia ago, in County Meath when the community buried this young woman.

In summary: The leading elder, a woman, chose a grave on the sunny side of the family enclosure so that the deceased would be connected to her kin in death, as in life.

When the rain cleared, the women lined up to take the body from the men, as it was tradition that they would bear her to the grave. They had washed and dressed her before the ceremonial procession and now they laid her in a grave, on her right side, wearing her best clothes, with sandals carefully placed on her feet.

She was in a crouched position, with her hands under her chin and her feet drawn up as if she were asleep. When they sprinkled water on her body and buried her under the wet earth, they knew she was ready to begin her journey in the direction of the setting sun, towards a new life.

It is unusual to read fictional accounts of prehistory, particularly in a book that covers 8,500 years of death - and life - in Ireland in such scholarly detail. But then Death in Irish Prehistory is an unusual book. It informs, surprises, and challenges in equal measure.

As the author so rightly points out, in the 10,000-year story of life in Ireland, we tend to focus on the most recent 1,500 years. In other words, three-quarters of the time that people spent on this island is given short shrift because there are no surviving documents from that time.

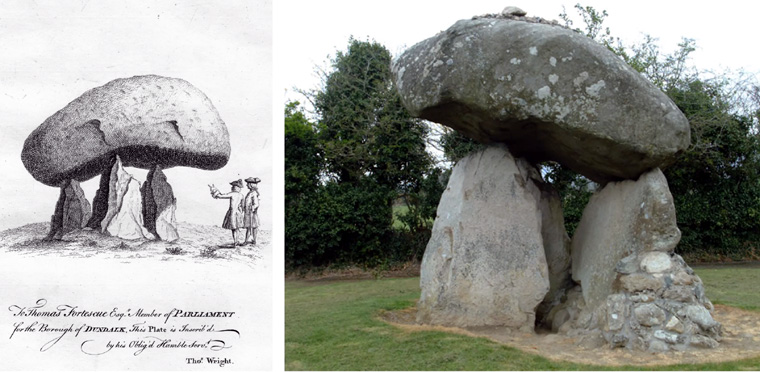

But here's the thing. It is documented, just not in a way that has been given the attention it deserves. The 'missing' 8,500 years of our history are inscribed in the landscape in the vast array of monuments that people built to honour their dead.

We can also get to know these forgotten people through their "stuff". Prof Cooney uses the word to explain the importance of archaeological artefacts - "the everyday bits and pieces that surround us" - and to explain what they tell us about those who used them.

He quotes Eavan Boland's poem The lava cameo to show how a grandmother's brooch, given as a gift by her husband, was passed down to become a family heirloom. In the process, it preserved an understanding of family history.

Archaeologists, he argues, do something similar. "Both archaeologists and poets try to tease out the complex webs of peoples' relationships with stuff."

I had never thought about that before. In the same way, I had never thought about how much we have ignored, or under-explored, so much of the Irish story.

Anyone with an interest in prehistory will be familiar with what Gabriel Cooney calls "the four-drawer filing-cabinet approach" to the past.

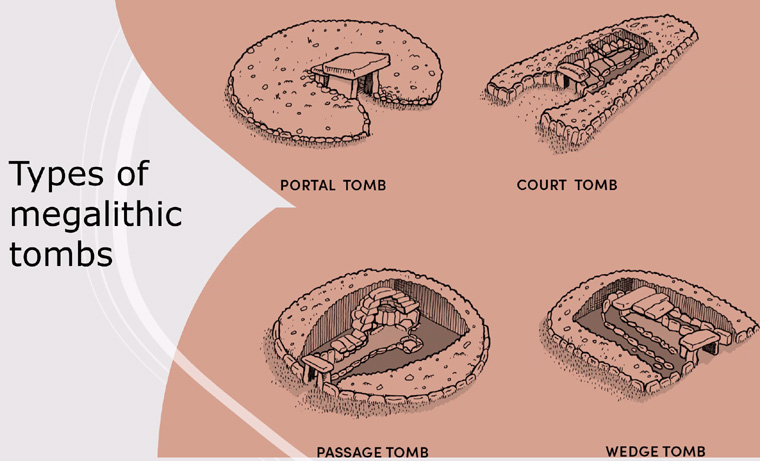

The Mesolithic (8000BC to 4000BC) describes the hunter-gatherer period. The Neolithic (4000BC to 2450BC) refers to the beginnings of farming and the construction of striking monuments to the dead, such as Newgrange and the passage tombs at Carrowkeel, so recently vandalised.

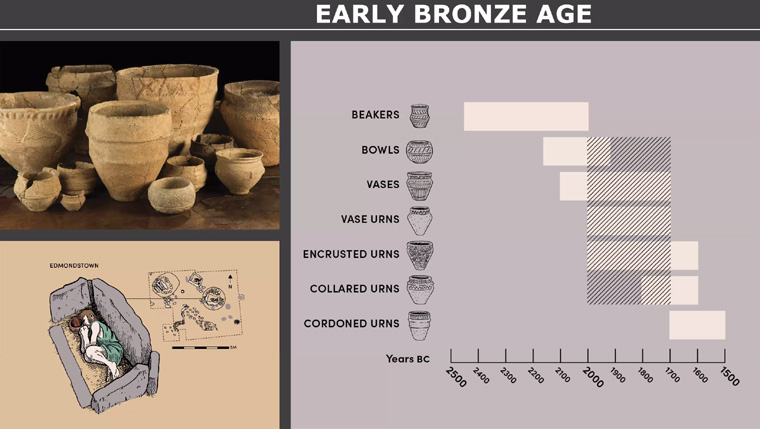

The Bronze Age (2450BC to 800BC) and the Iron Age (800BC to 400BC), as their names suggest, highlight the materials used in a new era of metalworking.

It is eye-opening to see an archaeologist of such note root around in those four drawers and present the evidence in such an accessible way.

Gabriel Cooney shatters the persistent myth that people in the past were somehow less culturally complex than we are. We tend to cast them in our own reflection, he says, and give them modern concerns.

He is also unafraid to focus on death which is so often hidden away from the everyday rather than seen as the "major, unifying existential issue facing us all, regardless of belief".

What is striking in reading a study of Ireland's first 8,500 years is the shared humanity that becomes evident from the way our ancestors treated their dead, or at least the small proportion of remains that have survived and been discovered.

Attachment to place is thousands of years old. So too is the veneration of human remains. In the Catholic faith, the relics of saints continue to unite the faithful. When the relics of St Thérèse of Lisieux went on tour in Ireland, thousands gathered to touch the casket carrying her bones.

In the same way, at several phases in the past, certain human bones, skulls in particular, were treated with reverence and seem to have been passed between members of the community. It is clear that these people had religious beliefs which informed their sense of social identity and their connection to the land.

Looking at the dead also tells us so much about life. Sometimes, in rather obvious ways. For example, the bones of a woman in an Early Bronze Age grave in Oldtown, Co Kildare, reveal she had osteoarthritis in her knees and was probably right-handed. Stress lines in her teeth enamel show that she suffered food shortages as a child. And she used her teeth as a tool, as the chip marks on her lower incisors attest.

Gabriel Cooney homes in on the particular, but he also provides a much bigger picture, which is breathtaking in its sweep. If there is a single unifying theme, it is that the past is always present. The people we love remain with us in our memories.

It is also clear that the Irish flair for poetry and funerals has a long history, as Thomas Lynch, poet and undertaker, said at the book's launch, which aptly took place on November 1, the feast of All Saints. "The Irish know what to do when there is a body in the room," he said, adding that this book (published by the Royal Irish Academy) illuminates the root of that excellence.

Speaking of excellence, when Bad Bridget by Elaine Farrell and Leanne McCormick was published last February, it struck me as a very important book that charted new territory. I'd say the same of Death in Irish Prehistory. It is sumptuously illustrated by Conor McHale; it wears its scholarship lightly and it offers the general reader an unrivalled insight into the first, overlooked eight millennia on this island.

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Visitor Centre

| Tours

| Winter Solstice

| Solstice Lottery

| Images

| Local Area

| News

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Articles

| Art

| Books

| Directions

| Accommodation

| Contact