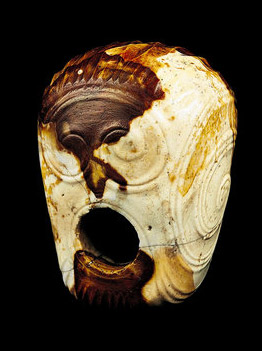

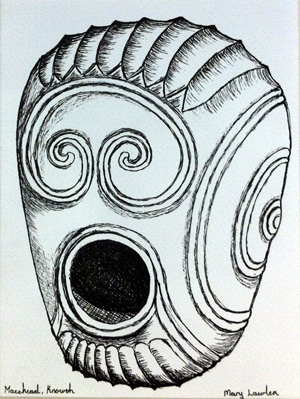

Knowth Flint macehead, 3300-2800 BC

By Fintan O'Toole from The Irish Times 'A history of Ireland in 100 objects' series.

This ceremonial macehead, found beneath the eastern chamber tomb at the great passage tomb at

Knowth, in the Boyne Valley, is one of the finest works of art

to have survived from Neolithic Europe. The unknown artist took a piece of very hard pale-grey flint,

flecked with patches of brown, and carved each of its six surfaces with diamond shapes and swirling spirals.

At the front they seem to form a human face, with the shaft hole as a gaping mouth.

This ceremonial macehead, found beneath the eastern chamber tomb at the great passage tomb at

Knowth, in the Boyne Valley, is one of the finest works of art

to have survived from Neolithic Europe. The unknown artist took a piece of very hard pale-grey flint,

flecked with patches of brown, and carved each of its six surfaces with diamond shapes and swirling spirals.

At the front they seem to form a human face, with the shaft hole as a gaping mouth.

If it was made in Ireland, the object suggests that someone on the island had attained a very high degree of technical and artistic sophistication.

The archaeologist Joseph Fenwick has suggested that the precision of the carving could have been attained only with a rotary drill, a "machine very similar to that used to apply the surface decoration to latter-day prestige objects such as Waterford Crystal". If this is so - and it is hard to understand how the piece could have been made otherwise - the technology predates that used in the classical world by 2,000 years.

The association of this extraordinary work with one of the great passage tombs tells us something about the society that constructed those enduringly awe-inspiring monuments. It was rich enough to value highly specialised skills and artistic innovation. And it was becoming increasingly hierarchical, with an elite capable of controlling large human and physical resources.

Knowth and the other great tombs were statements. As the archaeologist Alison Sheridan puts it, "Quite simply, they were designed to be the largest, most elaborate and most 'expensive' monuments ever built."

The insertion of a fabulous object like the macehead added to the sense that they were "a means for conspicuous consumption, designed to express and enhance the prestige of rival groups".

Knowth and the other great tombs were statements. As the archaeologist Alison Sheridan puts it, "Quite simply, they were designed to be the largest, most elaborate and most 'expensive' monuments ever built."

The insertion of a fabulous object like the macehead added to the sense that they were "a means for conspicuous consumption, designed to express and enhance the prestige of rival groups".

This prestige was asserted in the tombs in three ways. One was the possession of awe-inspiring objects like this one. The second was the use of astrological knowledge to demonstrate a link with the celestial world and the passage of the seasons, what Sheridan calls a hotline to the gods. A phallus-shaped stone, also found at Knowth, suggests that fertility rituals were part of this mystique.

The last aspect of this elite prestige was the demonstration of international connections. While small tombs like that in Annagh (see below) honoured local heroes, the great tombs were self-consciously European. There are strong parallels between the tombs and passage graves on the Iberian peninsula and in northwest France.

The likelihood is not that the tomb-builders came from these places but that they were part of a network of Atlantic connections. Already in Ireland a strong sense of the local coexisted with a desire to be seen as part of the wider world.

Neolithic bowl, c 3500 BC

The bowl is simple enough, very dark with burnished surfaces and relatively crude lattice-pattern decorations.

It was probably used for drinking and similar vessels have been found elsewhere in Ireland.

The bowl is simple enough, very dark with burnished surfaces and relatively crude lattice-pattern decorations.

It was probably used for drinking and similar vessels have been found elsewhere in Ireland.

Yet, because of the context in which it was found, this everyday object is extraordinarily eloquent. It tells us a great deal about the lives of some of the earliest Irish farmers.

It was discovered along with remains of three other pots in 1992 in a small cave in Annagh, north County Limerick, that contained three full human skeletons, two other sets of partial remains, various animal bones and a flint blade and arrowhead. The pots tell us that the people were farmers. The other objects tell us that they were also hunters and warriors.

Two big things thus emerge from this ancient grave. One is the reality that the development of agriculture was accompanied by considerable violence. The other is that it didn't happen all at once, that socially and culturally people retained their links to an older, wilder way of life.

Clearing land was hard work: the skeletons, which are all those of men, show the wear and tear of vigorous lives and the carrying of heavy weights. This hard-won territory had to be defended, and conversely offered an attractive prize for outsiders.

The men who were chosen for burial at Annagh seem to have been veteran local champions or heroes. They had survived a long time: two of them were into their 50s when they died - perhaps 20 years older than the norm. And they had survived serious violence. Two had serious head injuries, one a broken nose, one a fractured rib. In one case, the blow to the skull was delivered with such force that it must have come from something like a slingshot. Beside the plain domesticity of the bowl, there are the vestiges of brutal struggles.

The grave dates from the same era as the grand passage tombs such as Newgrange, but may reflect the continuation of older cultural practices. In this regard, the careful arrangement of hunter's apparatus (blade and arrowhead) with a selection of animal bones is particularly resonant. The animal bones were brought specially to the cave, and they represent both the old, wild world and the new order of agriculture.

On the one hand, there are bones from a bear, a wolf, a wild boar and a deer - creatures of the forest. On the other, there are bones of sheep and cattle - the domestic beasts raised by farmers.

Raghnall O Floinn of the National Museum, who led the excavation at Annagh, believes that this arrangement is deliberate and indicates a culture that is still in the midst of a long transition. Farming was the dominant way of life, but the call of the wild was still heard. Even as they cleared land and herded cattle, these local heroes may still have thought of themselves as proud hunters.

Ceremonial Axe, 3600 BC

Even now, its sheen and colour are magnetically alluring, the jade green surface, mottled with darker veins and glimmers of light, polished to a high sheen.

The shape is beautifully balanced between sharp edges and elegant curves. It was once thought that it must have come from China.

But if it looks exotic and mysterious now, 5,000 years ago in Ireland it would have seemed astonishing.

Even now, its sheen and colour are magnetically alluring, the jade green surface, mottled with darker veins and glimmers of light, polished to a high sheen.

The shape is beautifully balanced between sharp edges and elegant curves. It was once thought that it must have come from China.

But if it looks exotic and mysterious now, 5,000 years ago in Ireland it would have seemed astonishing.

The jadeite axe, from the Erris peninsula in County Mayo, was never used to cut anything. It was always a rare object, made to enhance the prestige of its owner. We now know just how exotic this one was: in 2003, it was established that the axe came from what was then an extraordinarily distant source: a quarry high in Mount Viso in the Italian Alps. It required enormous labour to mine and transport it. And it was already old - the manufacture of these specialist axes ended around 4,000 BC.

The axe tells us two big things. One is that Ireland was already part of a European-wide network. It travelled first to northwestern France, where it was polished. Then it made its way, either directly or through Britain, to west Mayo. And similar jadeite axes from Mount Viso were being imported into Denmark and Germany. The society that was emerging in Ireland was tangibly European, shaped by contact with the wider world. Mary Cahill of the National Museum believes that the axe may have been given as part of a "bride price" or dowry.

The second big thing is agriculture. Why is this ultra-prestigious object an axe? Because it was axes that allowed the dense woodlands to be cleared. The axe was the symbol of human power over nature. This piece of Italian exotica points us towards the single biggest transformation in Irish history: the adoption of farming shortly after 4,000 BC.

It is tempting to see the jade axe as evidence of new, Neolithic people coming to Ireland and bringing the revolutionary idea of farming with them.

Certainly, since the wild ancestors of wheat, barley, cattle and sheep did not exist on the island, they had to be introduced from the outside. But we simply do not know how this process happened, whether it was a slow evolution or whether it came as a package with new settlers. The scarce evidence tends to suggest a slow process - like the long progress of the axe itself from Italy to Ireland.

What we do know is that agriculture changed everything. It transformed the landscape, with the clearing of trees to make way for cereals and pasture. The introduction of domestic beasts doubled the number of large mammal species on the island. Farming created larger-scale settled communities with a strong sense of territory and ownership. And it created chieftains rich enough to own a fabulously exotic object.

Mesolithic fish trap, circa 5000 BC

It doesn't look like much: some small, smooth interwoven sticks embedded in the turf from a bog at Clowanstown, in County Meath. Its discovery was a side effect of the great Irish boom: it lay in the path of the M3 motorway. But at the end of the last ice age the bog was a lake. The woven sticks are an astonishing survival, part of a conical trap used by early Irish people to scoop fish from the lake or catch them in a weir. Radiocarbon tests date its creation to between 5210 and 4970 BC.

Mesolithic fish trap, circa 5000 BC

Mesolithic fish trap, circa 5000 BC

The delicacy of the work has survived the millennia. Nimble hands interlaced young twigs of alder and birch, gathered from the edge of dense woods. The warp-and- weft technique is quite advanced and similar to the way of weaving cloth that would be developed much later in human history. The Irish trap could be called a classic design: similar ones are still in use around the world.

The people who made this trap were adept at using what was around them. They used saplings to make circular tent-like huts. They turned flint and chert stones into knives, arrow heads and hand axes. They foraged, hunted and fished, gradually making a human mark on what had been an outpost of untouched nature.

In human terms Ireland is a very new country. Recent finds suggest the movement of our species out of Africa may have begun more than 125,000 years ago. North America was extensively settled 13,000 years ago. But there is no evidence of human settlement in Ireland before 8000 BC. Ireland was a remote island. It was also very cold, with the last of its ice ages not ending until 10000 BC. If small groups of people lived here during the warmer intervals, no trace of them has yet been found.

When hunter-gatherers did arrive from Britain, they found a densely forested landscape, a temperate climate and an abundance of animals, including wild pigs, wolves, foxes and bears (though not yet deer). Brown trout, salmon and eel were abundant in rivers and lakes. It is not accidental that the earliest settlements yet identified, at Mount Sandel, in Co Derry, and Lough Boora, in Co Offaly, were close to water: 70 per cent of the bones found at Lough Boora were from fish.

The people who made the trap almost certainly moved with the seasons, following their best sources of food. They would not have seen themselves as belonging to a large, overarching group. Yet the flint tools they made were gradually becoming distinctive and different from those in Britain. Slowly and unconsciously, Ireland was emerging as a particular human space.