Wakeman's handbook of Irish Antiquities

Revised and updated by John Cooke, 1903 It

was not without hesitation that I undertook, at the request of the proprietors and

publishers, the task of revising the previous edition of this work. To enter upon the

wide field of Irish archaeology I thought no easy task; but it was all the more difficult,

to my mind, from a sense of the qualifications required for revising the work of; one who was an

acknowledged authority on the subject. Every student of Irish archaeology is well aware of the extent of the

valuable contributions, by pen and pencil, of the late William Frederick Wakeman to our knowledge of that

subject, to the study of which he devoted the whole of his long life.

It

was not without hesitation that I undertook, at the request of the proprietors and

publishers, the task of revising the previous edition of this work. To enter upon the

wide field of Irish archaeology I thought no easy task; but it was all the more difficult,

to my mind, from a sense of the qualifications required for revising the work of; one who was an

acknowledged authority on the subject. Every student of Irish archaeology is well aware of the extent of the

valuable contributions, by pen and pencil, of the late William Frederick Wakeman to our knowledge of that

subject, to the study of which he devoted the whole of his long life.

That his Handbook so quickly grew out of date, and that a revision was thus rendered necessary, is due, partly to the results of the stimulus given to the students of the present generation by the school of archaeology to which he belonged; but more especially to the work of British and European archaeologists, and the general application of the comparative method of treatment to the whole field of archaeological science.

I found on entering on the work of revision that the book required much in the way of recension, but still more in the way of addition. While adhering to the general plan and spirit of the book, and retaining as much as possible of Mr. William Frederick Wakeman's work, I have made changes in the arrangement which I thought advisable, and enlarged the scope of the book, so that, as far as possible, it might cover the whole of Ireland.

The greater portion of the book has, in consequence, been largely re-written and expanded throughout; and the chapters on Burial Customs and Ogam Stones, Stone Forts, Lake-dwellings, Stone and Bronze Ages, Early Christian Art, are practically new. I have tried, as far as the limits of such a work would permit, to bring the book into line with recent research at home and abroad. The chapter on Raths and Stone Forts was written before the publication of Thomas Johnson Westropp's valuable work on the Ancient Forts of Ireland and it was satisfactory to me to find that in such general conclusions as, in the present stage of our knowledge, it is possible to arrive at, I was substantially in agreement with him.

It has been too much the custom in the past to look upon Ireland as being especially favoured with a wealth of antiquities. Pagan and Christian, more or less indigenous to the soil, and independent of the successive waves of influences sweeping from the Mediterranean littoral, and from Central Europe, ever westward and northward. Light can be thrown on problems still unsolved only by following the more scientific method of inquiry pursued, and by applying to them the knowledge gained in the wider field of European research.

Much yet requires to be done in the way of scientific exploration in Ireland; research work to be of any real value should be carried on only under expert supervision. That so much has been accomplished in the past is creditable to individual enterprise; but the time has surely come, with such examples before us abroad, that all further and extended investigation should be conducted under the superintendence of some recognised archaeological authority. An Archaeological Department is much needed in Ireland; and valuable scientific work of the kind in question should no longer be left to the haphazard enterprise of the amateur, however laudable that enterprise might be.

Still more is it necessary that some check should be put on such mischievous undertakings as the exploration of Tara Hill by those absolutely unskilled in archaeological work, and for the fanciful object, too, of discovering the Ark of the Covenant! Such 'Remains' as Tara are a national possession, a great trust from the past; and the sense of enlightened public opinion should make itself felt, in demanding such a protective measure as would ensure that the passing custodians, for their own day, of all like antiquities should not be allowed to injure them with impunity.

Over sixty new illustrations have been added to the present edition of this book. I am especially indebted to the Council of the Royal Irish Academy for the use of a large number of illustrations in the chapters on the Stone and Bronze Ages, Burial Customs, and Lake-dwellings; to the Council of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, for permission to use and reproduce several illustrations and plans; to Colonel Wood-Martin, for the use of illustrations from his several works on Irish Archaeology; to Mr. John Murray, for the illustration and plans of Newgrange; to Mr. Edward Stanford, for permission to use the plan of Tara from my edition of Murray's Handbook for Ireland; to the Secretary and Board of Education (England), for the illustration of Monasterboice High Cross; to them and to Dr. Joyce, for the illustrations of the Chalice of Ardagh, the Cross of Cong, and Tara Brooch ; and to the Rev. Maxwell Close, for details as to the measurements of several of the cromlechs and weights of the covering stones; also for the photograph from which the block of Kernanstowncromlech has been prepared. Some of the plans, and the illustrations of the Clonmacnoise Crosses (taken from Petrie's Christian Inscriptions), are the work of Miss Ivy H. Cooke; the wood-blocks from these have been prepared by Mrs. Watson. To my friend Mr. S. A. 0. Fitzpatrick I am again indebted for his great kindness in reading the proof sheets of this book.

It is hoped that it will supply the want felt by many interested in Irish archaeology — an interest evidenced by the maintenance of their usual high standard, in the publications of the Royal Irish Academy and the Royal Society of Antiquaries, and by the foundation in recent years of five provincial Archaeological Societies, whose excellent publications deal more especially with their several fields of research. My indebtedness to the publications of the two former Bodies is apparent by references in the footnotes.

For the sake of convenience of reference, I have referred throughout to the publications of the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, later the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association, and now the Royal Society of Antiquaries, under the last-named title, giving the year in each instance. An Index to the whole series of their Journal has just been completed by the Society.

John Cooke

Dublin

January 1903

Excerpt from Chapter 1 - Stone Monuments

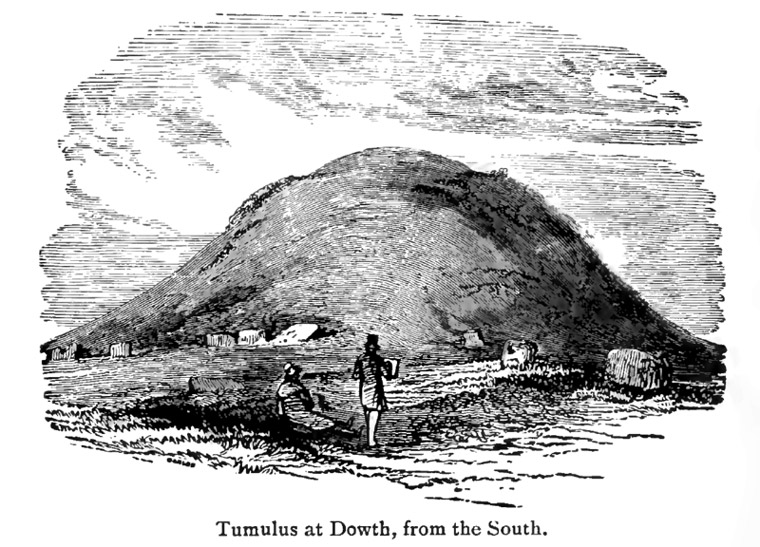

Ireland is, perhaps, more remarkable than any other country in the West of Europe for the number, the variety, and, it may be said, the nationality of its antiquarian remains. An archaeologist upon arriving in Dublin will find, within ready access of that city, examples, many of them in a fine state of preservation, of almost every structure of archaeological interest to be met with in any part of the kingdom. Sepulchral tumuli — several of which, in point of rude magnificence, are admitted to be unrivalled in Europe — cromlechs, pillar-stones, cairns, stone circles, and other remains of the earliest archaeological periods in Ireland, lie within a journey of a couple of hours of the metropolis. The cromlechs of Howth, Kilternan, Shanganagh, Mount Venus, Hollypark, Shankill, and Brennanstown (Glen Druid) are within easy reach of the suburbs of Dublin.The county has several round towers, and many churches of a very primitive type. An hour's journey by the Great Northern Railway to Drogheda, with a car drive of about twenty miles, affords not only an opportunity of seeing the great prehistoric remains of Newgrange and Dowth, but of viewing at Monasterboice, amongst other remains, two crosses, which are amongst the finest in Christendom. In the National Museum, Dublin, will be found the Royal Irish Academy collection of weapons and implements of the New Stone and Bronze periods, gold ornaments, crannog remains, Ogam stones, and relics of early Christian Art, which, we think it is not too much to say, is one of the finest and most representative that any country in Europe can show.

Irish Antiquarian remains may be generally classified under three heads: — 1. Prehistoric, embracing those which are considered to have existed previous to, or within a limited period after, the introduction of Christianity in the fifth century; 2. The Early Christian; and 3. The Anglo-Irish.

The Prehistoric remains consist of cromlechs, pillar-stones, cairns, stone circles, tumuli, raths, stone forts, beehive huts, rock-markings and weapons. They are found in considerable numbers particularly in the more remote parts of the island, where they have been suffered to remain, many more or less unmolested, save by the hand of time.

Early Christian remains are very numerous, and consist of oratories, churches, round towers, Ogam stones, and crosses. Of the early churches of Ireland — structures of a period when the 'Scottish (Irish) monks in Ireland and Britaine highly excelled in their holinesse and learning, yea, sent forth whole flocks of most devout men into all parts of Europe' — there are examples in a sufficient state of preservation to give a good idea of architecture, in what may be considered its second stage in Ireland.

The remains of what may be termed 'Anglo-Irish' structures were erected about the period of the English invasion, and although of Irish foundation, they appear generally to have been built upon Anglo-Norman or English models. The great barons who, in the time of Henry the Second, or of his immediate successors, received grants of land from the Crown, erected fortresses of considerable strength and extent, in order to preserve their possessions from the inroads of the native Irish, with whom they were usually at war.

The castles of Howth, Malahide, Maynooth, Trim, Carlow, and many others, are silent witnesses to the fact that the early invaders were occasionally obliged to place some faith in the efficacy of strong walls and towers to resist the advances of their restless neighbours, who, for several centuries subsequent to the Invasion, were rather the levellers than the builders of castles. Of the massive square keep, so common in every part of the kingdom, but especially within the English Pale, the Dublin neighbourhood furnishes several examples. As, except in some minor details, they usually bear a great resemblance to each other, an inspection of one or two will afford a just idea of all. They were generally used as the residence of a chieftain, or as an outpost dependent upon some larger fortress in the neighbourhood. Many appear to have been erected by English settlers, and they are usually furnished with a bawn, or enclosure, into which cattle were driven at night, a precaution very significant of the times.

The abbeys, though frequently of considerable extent and magnificence, are in general more remarkable for the simple grandeur of their proportions. The finest exhibit many characteristics of Transition style; but Early Pointed is also found, and in great purity. There are in Ireland but few very notable examples of the succeeding styles. Decoration, indeed, was not so much desired as strength and security; and we do not require the testimony of the 'Irish Annals' to show that the church buildings had occasionally to stand upon their defence: the bartizans surmounting the doorways of some, and the crenellated walls of many, are sufficient evidence of this.

There are certain antiquities which cannot well be classed with the remains referred to in the three preceding headings. Many of the lake-dwellings, or crannogs, for instance, are believed, with good reason, to have been in use even in pagan times in Ireland; some of these artificial islets were used in medieval times, and several are recorded to have been occupied as places of human habitation so late as the seventeenth century. It would, therefore, be hazardous to classify them with either pagan or Christian remains, and it is certain that they are not Anglo-Irish. A description of these will, however, be given in a subsequent chapter.

Pillar-stones or Dallans are found in many parts of Ireland, and particularly in districts where stone circles, cairns, and cromlechs occur. They are usually rough monoliths, and evidently owe their upright position, not to accident, but to the design and labour of a primitive people. They are usually called by the native Irish, Gallauns' or 'Leaghauns,' and in character they are precisely similar to the hoar-stone of England, the hare-stane of Scotland, the maen-qwyr of Wales, and the Continental menhir.

Many theories have been advanced with respect to their origin. They are variously supposed to have been idol-stones, to have been erected as landmarks, and as monumental stones recording the scene of a battle, or the spot upon which a warrior had fallen. The name 'cat-stone,' by which some examples are known in Scotland, would well warrant such an idea, the word 'cath' in the Gaelic language signifying a battle. At either end of the historic ford over the river Erne, at Ballyshannon, may be seen two remarkable examples — to that on the northern side other stones would seem to lead. This is a significant fact in favour of the landmark theory.

At the same time, we learn from the later writers of the life and labours of St. Patrick in Ireland, that he found the people worshipping certain idols in the form of stone pillars, some of which he caused to be overthrown, while upon one purposely left standing he inscribed the name of Jesus. There can be little doubt that the saint and his immediate followers, in their horror of all that was idolatrous, destroyed a large number of the pillar-stones which had been venerated and worshipped in pagan Ireland; but, nevertheless, a considerable number still remain. These, in some instances, would seem to have been consecrated to the Faith, and from having been idols were transformed into memorials of the triumph of Christianity.

We are not without satisfactory evidence of such adaptation having been effected. Several, and apparently the oldest, lithic monuments may be observed rudely punched, not carved, with the figure of a primitive cross, accompanied by one or other of the inscriptions DNI, DNO, or DOM. Todd, in his Life of St. Patrick, has, we believe, conclusively shown the generally received idea of the sudden, and, it may be said, miraculous conversion of Ireland in the days of the saint, and in those of his immediate successors, to be wholly erroneous. Pagan practices and beliefs long remained, and to-day many myths, legends, and superstitions attest, as dying remnants, how deeply rooted were the 'elder faiths.'

The Pillar-stone is the simplest form of all memorials; it is found in other countries in connection with ancient burial mounds or barrows. Such memorials to a departed hero, chief, or monarch were not confined to savage peoples, for the custom has descended through all stages of civilization, and the commemorative use of the pillar-stone is frequent in biblical history. Ancient Egypt furnishes notable examples of monoliths such as Cleopatra's Needle; while the metropolis of Ireland, not to mention other cities, exhibits stupendous pillar monuments showing the 'hero-worship' of our forefathers, to the dead leaders Wellington and Nelson.

In several parts of the country the gallaun is still considered by many of the people to be something weird, and, 'to be let alone.' The late E. A. Conwell, in his work on the supposed tomb of Ollamh Fodhla, points out that, about two miles north-west of Oldcastle, there is a townland called Fearan-na-gcloch (from fearan land, and cloch, a stone), so called from two remarkable stone flags, still to be seen standing in it, popularly called Clocha labartha, the 'Speaking stones' : and the green pasture-field in which they are situated is called Pairc-na-gclochalabartha, the 'Field of the speaking stones.'

'There can be little doubt,' he proceeds, 'the pagan rites of incantation and divination had been practised at these stones, as their very name, so curiously handed down to us, imports; for, in the traditions of the neighbourhood, it is even yet current that they have been consulted in cases where either man or beast was supposed to have been "overlooked"; that they were infalliblyeffective in curing the consequences of the "evil eye"; and that they were deemed to be unerring in naming the individual through whom these evil consequences came.

Even up to a period not very remote, when anything happened to be lost or stolen, these stones were invariably consulted; and in cases where cattle had strayed away, the directions they gave for finding them were considered as certain to lead to the desired result. There was one peremptory inhibition, however, to be scrupulously observed in consulting these stones, viz. that they were never to be asked to give the same information a second time, as they, under no circumstances whatever, would repeat an answer.'

These conditions having, about seventy or eighty years ago, been violated by an ignorant inquirer who came from a distance, the 'speaking stones' became dumb, and have so remained ever since. There were originally four of these stones: of the two that remain, the larger may be described as consisting of a thin slab of laminated sandy grit. Its dimensions are as follows: total height above ground, very nearly 7 feet; extreme breadth, 5 feet 8 inches; breadth near summit, 3 feet 6 inches; average thickness, about 8 inches. In no part does it exhibit the mark of a chisel or hammer. The height of the second remaining stone, above the present level of the ground, is 6 feet 4 inches; it is in breadth, at base, 3 feet 4 inches, and near the top 1 foot more; thickness at base, 14 inches. The material, unlike that found in the generality of such monuments, is blue limestone.

Wakeman's handbook of Irish antiquities

is a comprehensive guide to the rich history and culture of Ireland. Written by prolific author and writer William Frederick Wakeman,

this classic book is a must-have for anyone interested in the ancient and medieval heritage of the Emerald Isle.

Wakeman's handbook of Irish antiquities

is a comprehensive guide to the rich history and culture of Ireland. Written by prolific author and writer William Frederick Wakeman,

this classic book is a must-have for anyone interested in the ancient and medieval heritage of the Emerald Isle.

The handbook covers a wide range of topics, including prehistoric monuments, ancient burial sites, medieval churches, castles, and monastic settlements. Wakeman provides detailed descriptions and explanations of each site, drawing on his extensive knowledge of Irish archaeology and history. What sets this book apart is Wakeman's engaging writing style and his ability to bring the past to life. He delves into the myths and legends surrounding the sites, providing fascinating insights into the beliefs and traditions of the ancient Irish people.

Whether you are planning a trip to Ireland or simply want to delve into its rich history from the comfort of your armchair, Wakeman's handbook of Irish antiquities is an invaluable resource. It is a timeless classic that will continue to inspire and educate readers for generations to come.

Purchase at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

Boyne Valley Private Day Tour

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Immerse yourself in the rich heritage and culture of the Boyne Valley with our full-day private tours.

Visit Newgrange World Heritage site, explore the Hill of Slane, where Saint Patrick famously lit the Paschal fire.

Discover the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of power for the High Kings of Ireland.

Book Now

Home

| Visitor Centre

| Tours

| Winter Solstice

| Solstice Lottery

| Images

| Local Area

| News

| Knowth

| Dowth

| Articles

| Art

| Books

| Directions

| Accommodation

| Contact